Future (Pet) Sematary

Our Halloween take on dead people and pets

Today is Halloween, and we are asking a fitting question: what should we do with the bodies of the dead?

Since ancient times, people have buried their tribesmen in the ground (apparently, Neanderthals did this too). But this method, once a simple sanitary procedure, is becoming increasingly inconvenient and impractical. Modern giant cities require more and more land for burials (in megacities, cemeteries can occupy 0.5–2% of the total city area) — about 60 million people die worldwide every year, and the Abrahamic religions, followed by more than half of humanity, often oppose the reclamation or relocation of old cemeteries.

It’s no coincidence that we mention religion here — as Western countries become more secular, more and more people there prefer cremation, while in Asian countries it has been dominant for centuries. It seems like a simple, eco-friendly, and hygienic alternative. Furthermore, other options, such as burial at sea or leaving bodies for birds to scavenge, are unlikely to scale well in the modern world.

But there is another option — to donate your body to science. This usually implies the use of bodies for medical purposes — for training medical students or research. However, we propose to consider another science — archaeology.

For archaeology, found skeletons and mummies are of immense interest — we learn about the health, lifestyle, diet, and physical exertion of people from the distant past. Thus, preserving the bodies of modern people becomes our responsibility to future generations. We do not know what will specifically interest our descendants. Furthermore, they will likely need a large sample size for substantiated conclusions. Therefore, it is logical to assume that we need to preserve all or almost all bodies, and do so with the highest quality possible.

Paradoxically, in doing so, we are in a way returning to the idea of the necessity of preserving the body after death, though now not in the hope of resurrection on Judgment Day, but with the noble goal of helping our descendants.

We can imagine two methods for the long-term preservation of bodies, both imperfect. Either freezing (or some similar preserving procedure), or digitization using a combination of methods (photography, MRI, CT, etc.). The drawback of the first method is that bodies will inevitably be preserved with some damage. Moreover, they will still take up a lot of space, which of course could be solved with dense, multi-story storage.

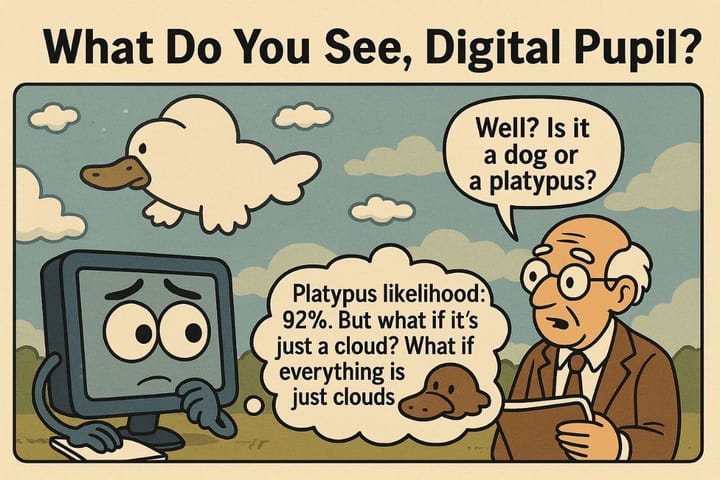

The second method suffers from the fact that we cannot fully digitize a human body. X-rays became available to doctors just over 100 years ago, MRI — about 50 years ago. We can assume that in another 50 years, new methods of “scanning” the human body will appear, allowing us to obtain information that is currently inaccessible. It is appropriate to recall here that up to half of the lunar soil delivered by the American Apollo missions was preserved for potential future research. The USSR followed the same practice, and now China does too.

Of course, digitization seems to be a much cheaper procedure — its cost can be estimated at several thousand dollars, which, given the number of people dying annually, would amount to, say, $100 billion — a figure comparable to global spending on space exploration. Freezing is one to two orders of magnitude more expensive, so this technology is clearly not yet ready for mass implementation.

How exactly could this help future people? For example, today we suspect that human biological evolution is continuing. It seems that more and more people are being born without wisdom teeth. A well-known 2020 study suggests that every year, more people are born with a third, median artery in their arm. Naturally, any such research is easy to criticize, as even data collection from 50 years ago is questionable. Both the sample size (the total number of people studied) and its reliability (only specific population groups might have come to the attention of medics) are easily criticized.

Why we need this artery, what advantages it provides — is not yet very clear. Perhaps the improvement in people’s well-being over the last two centuries plays a role, or perhaps warmer hands facilitate finding a sexual partner. In the case of mass body preservation, it would be easy for us to obtain high-quality statistical data, easily look for correlations with lifestyle, diet, and, ultimately, answer the aforementioned questions.

Of course, the same logic applies to domestic animals, from dogs and cats to parrots and cows. Breeders, geneticists, and zoologists would receive a huge array of data for research if we preserved the bodies of animals.

Comments ()