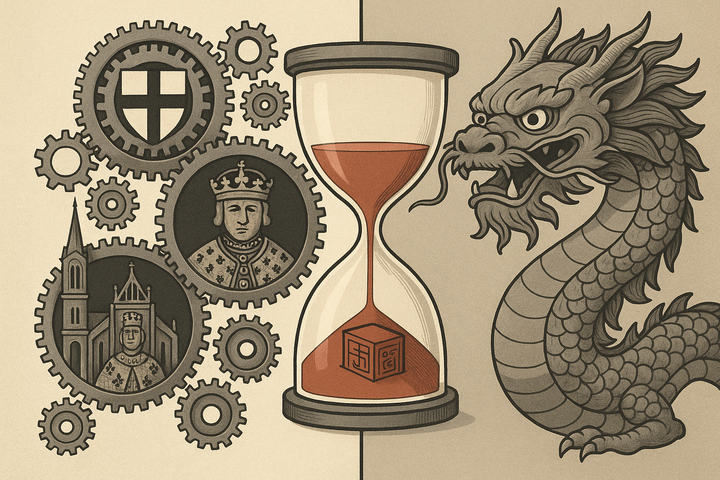

Has the Catholic Church prevented the unification of Europe?

The Papacy vs. Empire: A Medieval Power Struggle That Shaped Europe

The death and election of a new pope naturally draws attention to the Catholic Church and its role in history. For centuries it has remained the most influential institution in Europe. It is often accused of stifling science; less often, it is remembered for its role in preserving the ancient heritage that became the foundation of the Renaissance. And what can modern science tell us? We have previously discussed the role of the Church in the destruction of the traditional family in Europe (see Church and kinship), but could it also have been a major obstacle to the unification of Europe?

This is the subject of a recent article by Anna Grzymała-Busse, a political scientist who explores the influence of the Church on the political structure of Europe.[1]

How is the emergence of European states usually explained?

The most popular is the so-called “bellicist” theory. According to it, the fragmentation of Europe began after the collapse of the Carolingian Empire at the end of the 9th century. And modern states were formed as if only as a result of endless wars from 1500 to 1800. These wars, they say, required the creation of a powerful bureaucracy, tax system and army, and at the same time — the absorption of small principalities by strong centers of power. One of the fathers of this theory, Charles Tilly, put it succinctly: “war created the state, and the state created war”.

But if you dig deeper, a lot of things don’t add up. First, Europe remained fragmented until the mid-19th century (see Figure below) — despite supposedly strengthened states. Second, key institutions like parliaments, taxation, and centralized administration emerged before the era of major wars. And wars did not always strengthen states — they often destroyed them, as happened to France and Poland in the 18th century.

Still, the big question is: when did this very fragmentation of Europe begin in the first place? As Figure above shows, Germany and Italy “exploded” in 12th century. And that’s when the Catholic Church comes to the fore.

How the Church gained power

What happened at the beginning of the 12th century? The Church became sufficiently autonomous. Up to this point, local secular rulers had built churches, appointed clergy and received revenues from church lands, and the Holy Roman Emperors had even appointed Popes. Only after 1059, and especially during the reign of Pope Gregory VII, did the Church begin to gain autonomy, and the popes began to be elected by cardinals. The long struggle for the right to appoint bishops (the so-called struggle for investiture), which included many military conflicts, excommunications, and negotiations, culminated in the Concordat of Worms in 1122, which finally secured for the Pope the right to appoint bishops at his discretion.

Having freed the Church from the control of the emperors, the Popes began to intervene actively in secular politics, in particular to prevent the emergence of a new threat in the form of an overly powerful Empire.

Over the next two centuries, from about 1100 to 1300, the Catholic Church became the true hegemon of Europe:

— Wealth: The Church owned vast territories. Before the Reformation, it controlled half the lands of Germany and a quarter of England. It also levied the tithe, a compulsory tax of 10% of all income, which provided it with a steady and enormous flow of resources.

— Intellectual capital: Educated clerks, archives, lawyers, skilled in administration-all these made the Church indispensable to rulers.

— Moral authority: it regulated almost every aspect of life, from marriages to food. Excommunication from the Church meant social death.

How the Church hindered consolidation

Anna Gzymala-Busse argues that the political fragmentation of Europe (primarily Germany and Italy) was the result of a deliberate policy of the Church. To prevent the consolidation of secular power, especially by the Holy Roman Empire, the Church:

- supported free cities,

- made alliances with princes and rebels,

- provoked and sustained conflict,

- punishing rulers who were too powerful.

Indeed, conflicts involving the Church peaked between 1100 and 1300 (see Figure below). When its influence waned, the number of religious wars declined sharply.

On the contrary, where the Church supported central authority or simply did not intervene — England, France, Spain — states consolidated more quickly.

What the data showed

To test the hypothesis, the researchers divided Europe into 100×100 km squares and counted how many borders run through each one. This can be used as a measure of fragmentation (we talked about similar technique in War and Urbanization).

And then compared the data with the frequency of religious and secular conflicts, the spread of parliaments and other institutions.

The result:

- Religious conflict correlates with fragmentation.

- Parliaments, conversely, are associated with larger states.

- Secular wars had almost no effect on the level of fragmentation.

Funny outcome

In trying to maintain power, the Church unwittingly created the conditions for its own weakening. By the 16th century, the German princes had so much power that they were able to support the Reformation — and refuse to submit to the pope. Strong local power proved immune to spiritual dictates.

Conclusion

To understand why Europe did not become a unified state like China or the Arab Caliphate, we need to look not at wars, but at the interaction of spiritual and secular power. The Catholic Church played a much more active role in shaping the map of Europe than is commonly thought. But why was its policy exactly that? Why did analogs of the Church not emerge in other parts of the globe?

References:

1. Grzymala-Busse, Anna. “Tilly goes to church: the religious and medieval roots of European state fragmentation.” American Political Science Review_ 118.1 (2024): 88–107.

Comments ()