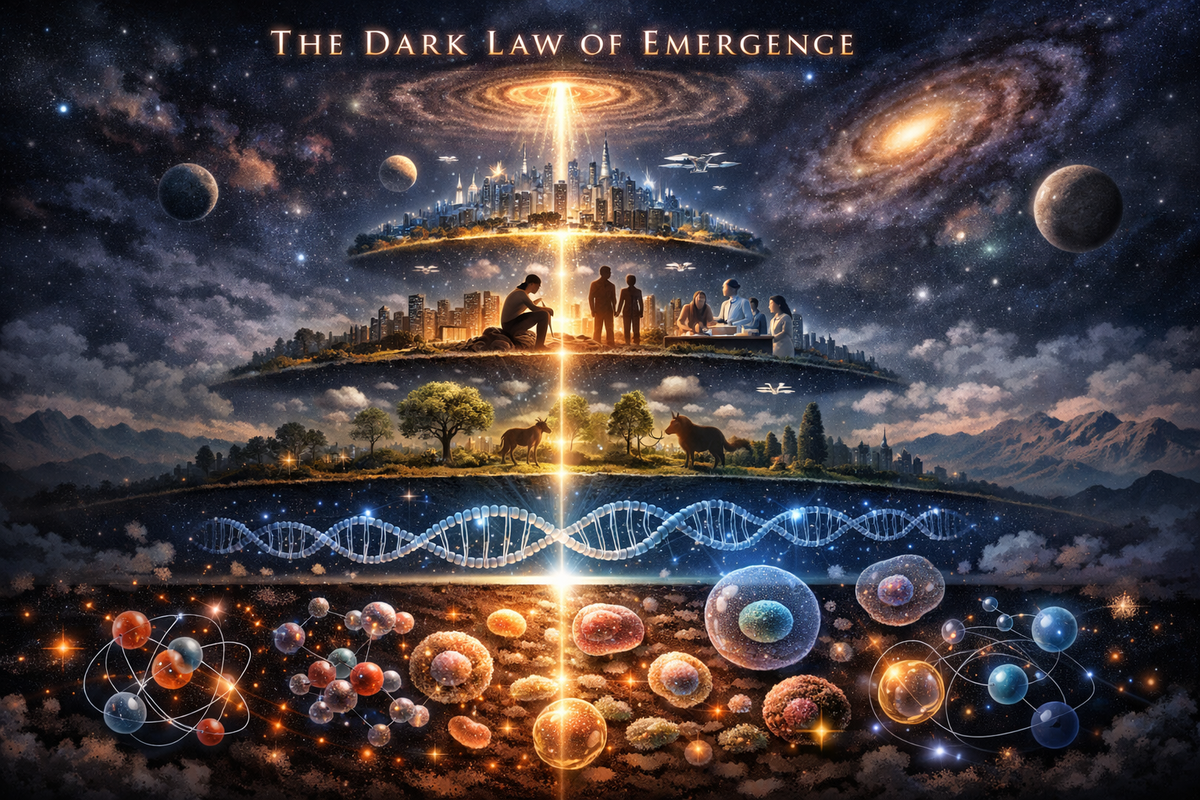

The Dark Law of Emergence

We are used to believing that by breaking a whole down into its tiniest parts, we can understand its essence. But what if the opposite is true? What if, by diving into the smallest details, we hopelessly lose the very phenomenon we seek to understand?

This post is inspired by the book "A Different Universe: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down" by Nobel laureate in physics, Robert Laughlin.

As we explored in a previous post, many physical quantities and—more importantly—entire physical laws are emergent. Their nature is tied to the collective behavior of objects, not to the properties of the individual objects themselves. The very existence of solid bodies is emergent! And of course, the different states of matter—solid, liquid, magnetic, superconducting—are pure examples of emergence.

The qualitative properties of these states are practically independent of the material. Their universality and precision leave no room for a microscopic explanation. Everything is determined by the architecture of interactions, not by the individuality of the particles. Any liquid fiercely equalizes a pressure difference. Any metal elastically resists deformation. Add impurities and these fundamental responses remain unchanged. This points to a remarkable fact: nature possesses guardian laws that protect higher-level order from the chaos at the level of individual particles.

A great example of this protection is scale invariance—the independence of certain laws from size. Many laws actually do depend on size. A plane twice as big does not fly twice as far. An animal with a brain twice as heavy as a human's is not two times more intelligent. Yet in many cases laws are indeed scale-independent.

Let's conduct a thought experiment. A director is filming the sound of an organ pipe. Dissatisfied with the first take, he decides to double the size of the pipe. To fit it in the frame, the cameraman steps back twice as far. The pitch of the sound drops, of course, but this is fixed by doubling the playback speed of the recording. And the discovery: the new footage is indistinguishable from the original!

The reason is that the laws of hydrodynamics governing the sound in the pipe are scale-invariant. This is precisely why engineers can test tiny models of airplanes in wind tunnels—the laws of airflow are the same for the model and the giant in the sky.

But this magic of scale is not universal. It extends infinitely towards larger sizes but breaks down at the boundary of the atomic world. The laws of hydrodynamics, like many others, are emergent, born from the collective behavior of trillions of particles. A single, isolated atom does not know whether it will become part of a solid, liquid, or gas. That is decided only by their collective "crowd." Yet, paradoxically, the type of that atom matters little for the sound of the entire organ.

From these examples grows the idea of the Barrier of Relevance. To grasp its essence, let's take a brief but crucial detour into the world of chaotic systems.

For a long time, classical physics naively believed: measure the initial state of a system precisely enough and you can predict its future indefinitely. It was thought that small measurement errors would eventually "wash out" and not affect the final outcome.

However, in the 1950s, systems with the opposite behavior were discovered, systems where errors only accumulate and amplify over time (though mathematicians had known of their existence earlier). The classic example of such a system is the weather. Using satellites and weather stations, we gather information about the current state of Earth’s atmosphere—temperature, pressure, humidity, and countless other parameters—at numerous points. Crucially, every one of these measurements comes with its own margin of error, and the number of points where they’re taken, while large, is vanishingly small compared to the sheer number of points that make up the entire atmosphere. Over time, these initial uncertainties grow, limiting our ability to forecast the weather to just a week or two ahead. But the most troubling property of chaotic systems is this: even if we improve the accuracy of our initial measurements tenfold, the forecasting horizon expands only marginally—say, merely doubling.

Surprisingly, climate, which seems to be just "weather on average" over long scales, turns out to be much more predictable and obeys different, more stable laws.

It's noteworthy that the chaotic nature of a system cannot be strictly proven—it can only be detected. If a system's final state demonstrates extreme sensitivity to the tiniest changes in initial conditions, that is the practical signature of chaos.

Let's return to the Barrier of Relevance—the very "dark law" of emergence that Laughlin speaks of. He proposed a key idea: a pattern similar to chaos may manifest not only in evolution over time but also in "evolution across scale." Even possessing nearly complete information about individual particles, we hopelessly lose the ability to predict an object's properties as the number grows. Upon crossing an invisible complexity barrier, microscopic information becomes "noisy," and fundamentally new rules of the game are born. This law is "dark" since it conceals the deeper nature of things from an observer, and hides irrelevant microscopic details.

We cannot prove this rigorously, but many facts suggest that almost all real physical systems are structured this way. Recall: not a single attempt to derive Newton's second law from quantum mechanics has succeeded. Not one of the known phases of matter (liquid, solid, superconductor) was predicted theoretically. They were all first discovered experimentally. Thus, our flawless theories of the micro-world are, in practice, powerless to describe the properties of macroscopic objects, even though, ironically, they form their very foundation.

If this "dark law" and barrier exist, what conclusions must we draw? Their significance is hard to overstate.

First, it is a crushing blow to reductionism—the idea that by understanding the smallest parts, we understand the whole. Even if a "theory of everything" is found, it will be powerless against the questions of hydrodynamics, chemistry, or biology. The Holy Grail of fundamental physics will not be the key to higher levels of complexity.

Second, it radically changes our picture of reality. It appears not as unified, but as multilayered and hierarchical. From the quantum foundation, we ascend a ladder of scales to chemistry, biology, society. Each level lives by its own laws, which are largely indifferent to the structure of the lower "floors." A computer can be built from transistors, gears, water tubes, or even a colony of mold. It will still obey the laws of computability, not the physics of semiconductors or biochemistry.

From this comes a powerful insight about intelligence. It has arisen independently in creatures as different as mammals, cephalopods, and social insects. There is no physical reason why it could not arise in electronic circuits. Therefore, to study it, it is not necessary to descend to the level of neurons. Neuroscience is a lower "layer" that determines the specific implementation, but not the essence of intelligence—that very ability to solve non-standard problems through learning.

It is here that the idea of emergence intersects with psychohistory, the hypothetical exact science of human societies. It ceases to be a mere speculative construct and becomes a logical consequence of the "dark laws."

On one hand, to build such a science, it seemingly does not require delving into the neurobiology or biology of an individual human. As with a liquid or intelligence, its laws must be born from collective interaction, not from the structure of individual "particles", i.e., people.

On the other hand, this means its laws must be truly universal, applicable to any human societies, in any historical epoch, and, ultimately even to extraterrestrial civilizations. Understanding aliens, in that case, becomes not a question of biology but a task of social mathematics, operating on the emergent patterns of intelligent collectives.

In conclusion, let's try to answer the question of what emergence is with a quote from Laughlin himself:

"Emergence means complex organizational structure growing out of simple rules. Emergence means stable inevitability in the way certain things are. Emergence means unpredictability, in the sense of small events causing great and qualitative changes in larger ones. Emergence means the fundamental impossibility of control. Emergence is a law of nature to which humans are subservient."

Comments ()