Why Polymaths Will Rule the Future

How AI will really change the course of human history

First published in tg-channel Cliomechanics in Russian

Specialization wasn’t always humanity's default mode. Our distant ancestors had no such luxury: survival demanded a diverse and constantly evolving skill set to adapt to ever-changing environments. Specialization emerged gradually, fueled by rising population density and societal complexity. It was a necessary response to the growing informational depth of skills, paired with our brain’s limited processing speed and the finite time available to learn.

Today, despite technology that accelerates information processing, each new layer of societal complexity spawns even narrower specializations. In the short term, this boosts efficiency in specific tasks. But in the long run, it fragments knowledge, weakening society’s adaptive resilience and—crucially—its creative potential.

Serious academic research shows a clear correlation: the breadth of a person’s interests and competencies is directly linked to their creativity. Most of history’s most brilliant scientists and entrepreneurs were polymaths at heart. Their constantly expanding knowledge from diverse fields allows them to build atypical skill combinations, integrate them, and generate breakthrough ideas—often birthing entirely new disciplines and industries.

Why does this seem counterintuitive? It shouldn’t be surprising. For most of human history, technological progress was limited not only by available energy but also by our capacity to create, process, transmit, and store information.

Not everyone is wired to collect and analyze vast amounts of heterogeneous data. And for most of humanity, there was never a need: the practical value of encyclopedic knowledge was often questionable, while the cost of acquiring it was high. Ironically, digital technology and the internet have worsened this by creating data oceans impossible to navigate with traditional methods.

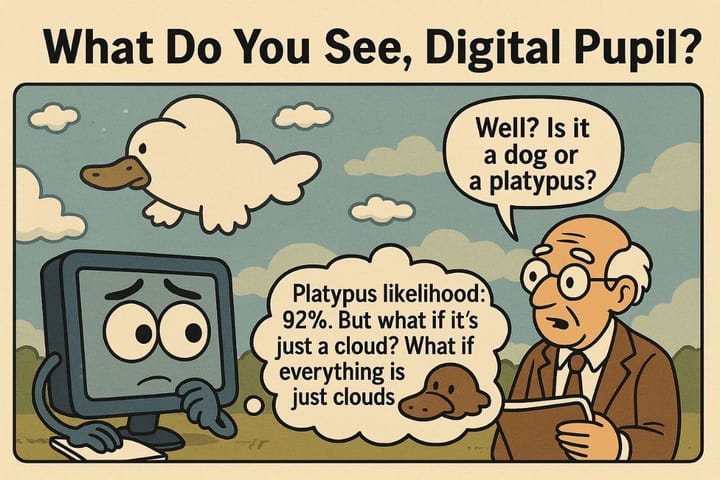

The solution emerged in the form of language models—colloquially called AI. They handle massive datasets, structuring and analyzing them at speeds unattainable due to our biological limits. This combination of speed and scale is reshaping our entire way of life before our eyes, including science, by fostering new industries and disciplines.

And here, our cultural evolution takes an unexpected turn. By performing routine work faster and better, these models are nullifying the value of specialization in many fields. Not everywhere and not all at once, but inevitably. They process volumes of information that would take a specialist fifty lifetimes to study. They can produce analyses or, through sheer brute-force computation, arrive at combinations overlooked by specialists or dismissed as too costly or futile—and find something valuable there.

In this new reality, creativity becomes intellectual capital. Content generation, now automated, creates a surplus of supply and devalues standard solutions. A creative, polymathic approach may shift from a nice-to-have to the ultimate competitive asset. The winners won’t be those who work faster, but those who can create new contexts capable of breaking through the wall of algorithmic predictability.

One way or another, a brave new world awaits.

Sources:

📚 Charles Murray. Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950.

📖 Michael Simmons. People Who Have “Too Many Interests” Are More Likely To Be Successful According To Research.

📖 Robert Root-Bernstein. Multiple Giftedness in Adults: The Case of Polymaths.

📖 Freeman Dyson. Birds and Frogs.

Comments ()