Why We Cling to Our Tribes

Ancient group-thinking is shaping modern politics

First published in tg-channel Cliomechanics in Russian

For most of human history, economic productivity was so low that survival was only possible within a group. But this collective existence came with conditions: collective labor, communal property, and the distribution of resources were inseparable from family, religion, and kinship.

The primary goal was not profit, but the optimal redistribution of scarce resources within the group to ensure its survival. Thus, the extended family or clan was first and foremost a mechanism for collective survival, not collective enrichment.

How does such a "tribe" function? It's built on mutual aid, strict hierarchy, and status-based distribution—all sanctified by tradition, morality, and religion. No one has excess; all benefits come from the group and return to it. The beauty of this system lies in its self-organization. It requires almost no resources to maintain the social structure itself. This is likely why it's so tenacious: it survives almost unchanged to this day in patriarchal families, peasant communities, religious sects, and criminal gangs.

The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss draws a clear line between this world and ours:

Primitive societies are governed... by kinship structures, not by economic relations. Had these societies not been destroyed from the outside, they could have existed indefinitely.

The rules of the game have been changed by the emergence of a surplus. When resources exceed mere survival needs, exchange emerges, and with it—an economy governed by the rules of a non-zero-sum game (where all participants can win). This triggers innovation, social complexity, and—key—the emergence of the free individual. This process destabilizes rigid kinship structures. (Previously we talked about an alternative suspect for this process — all-mighty Roman Catholic Church.)

But when a group finds itself on the brink of survival again, economics takes a back seat. Non-economic mechanisms kick in: forced redistribution, suppression of individual initiative. The higher the risk, the stricter the control. And the more likely the group is to play a zero-sum game with the outside world ("what we win, you lose").

Under harsh conditions, people tend to cooperate only within their own group and deeply distrust outsiders. The worse the perceived conditions, the narrower the circle of "us." Abundance (or at least the absence of acute scarcity) and a secure environment lower the degree of paranoia. They allow for building broader coalitions and trusting beyond kin.

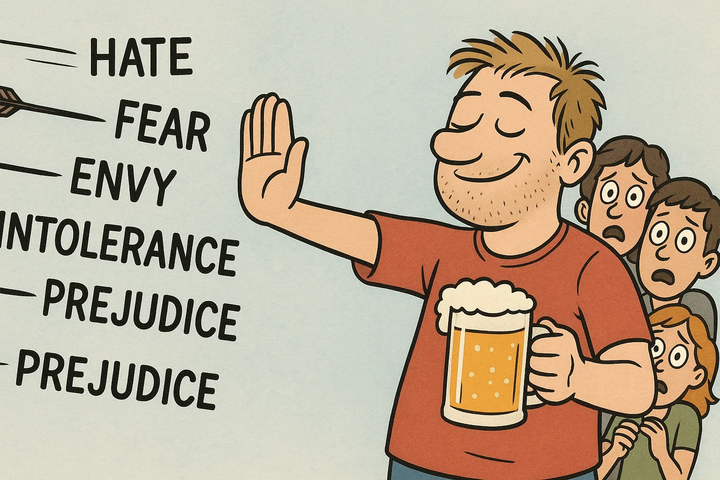

This view helps explain the rise of conservatism in modern societies undergoing economic strain, where there is a growing demand for:

- "Fair" redistribution

- The search for external enemies

- The protection of "traditional values" (often a nostalgic image of those same rigid in-group survival rules)

All this is an ancient social algorithm that activates when the collective brain perceives a threat to the group's existence.

Further reading:

📚 Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology

📚 Desmond Morris, The Human Zoo

📚 Robert Sapolsky, Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers

📖 Karpenko N.A., Game Theory Economics and Its Social Boundaries (in Russian)

Comments ()